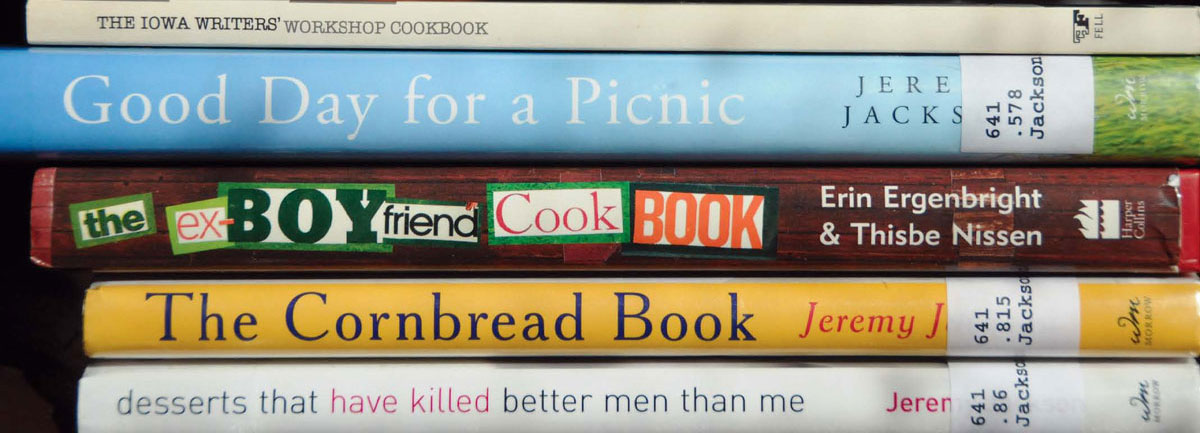

The (Food) Writers’ Workshop

A selection of food books from Iowa Writers Workshop Authors

The list of iconic works of literature — poetry, fiction, and nonfiction — crafted by writers who have been students or faculty (or both) in the Iowa Writers’ Workshop is, it perhaps goes without saying, impressive. You can count up the awards, peruse various “best of” lists, dip into a host of anthologies, or read many of the excerpts installed in Iowa City sidewalks if you need to be reminded of the power and range of writing that has a connection to the Workshop.

But in one arena, Workshop writers are perhaps not as celebrated as they ought to be. That arena, of course, is the cookbook. To remedy this oversight, we offer a roundup of Workshop-related cookbooks.

The Iowa Writers’ Workshop Cookbook, edited by Connie Brothers

Connie Brothers is a central figure in the lives of those who attend the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. She is the Workshop’s central staff member, and it is clear that she is a great influence on the many writers who pass through the program. Read the acknowledgments page of a debut book from a Workshop grad, and you are likely to find her name there.

The late Frank Conroy, director of the Workshop from 1987-2005, once called Brothers, “the best literary connected person I know.” She leveraged those connections in the mid-1980s to create The Iowa Writers’ Workshop Cookbook. The book features caricatures of the contributing authors by Peter Nelson.

Origins of the cookbook: “I thought of it over Christmas break when I didn’t have enough to do, apparently,” Brothers said.

Brothers realized that she talked about food with just about every student and faculty member in the Workshop, and it occurred to her that a Workshop cookbook might be a way to raise money for student scholarships. The members of the Workshop community—120 of them—were pleased to participate. “I was friends with all of them,” Brothers said, “so I just asked them, and they all said yes.”

In the end, the book didn’t make much money, certainly not enough to justify the complexity of the project. “It was so much trouble,” Brothers said, “I thought, what a stupid idea.”

But the book itself is a quirky delight, well worth seeking out for the glimpse it provides of these writers cooking up something served with a side of their own style and sense of humor.

Favorite Recipes: Brothers acknowledges that not all of the book’s recipes are traditional. “There’s a lot of them you wouldn’t want to make,” she said. But she did site a few favorites, including:

Tess Gallagher’s Pears á la Carver. The recipe includes this warning: “Now (Raymond) Carver will be standing behind you with a strange gleam in his eye. (Hopefully you’ve hidden two pears.)”—

Bob and Peg Dana’s Fettucine with Black Olive Sauce. Robert Dana recounts his history with the recipe, concluding: “A no-fail specialty. And what mathematical formula or poetic theory can rival that?”

Louise Glück’s Hamburger. This poem about what Leonard Michaels might contribute ends: “…you mash/it up with a fork, you flee.” Says Brothers, “It was so like both of them.”

The Cornbread Book, Desserts That Have Killed Better Men Than Me, and Good Day for a Picnic by Jeremy Jackson

Jeremy Jackson, a Workshop alum who still resides in Iowa City, is the author the novels Life at These Speeds and In Summer He also writes young adult fiction under the pen name Alex Bradley.

Origins of the cookbooks: “I stumbled into writing cookbooks,” Jackson said. “I had been writing fiction for a long time, but writing cookbooks wasn’t on my radar at all. But I kept thinking to myself that someone should write an entire book about cornbread. Finally, I realized that the someone was me.

In the introduction to his second cookbook, Jackson relates a similar story:

“…I was constantly inventing titles for cookbooks that I might write someday…Most of the titles I came up with were useless, like My Damn Meat Loaf, Desserts You Can Mail, and The Scratch and Sniff Cookbook. But one title, Desserts That Have Killed Better Men Than Me, struck me immediately as being fantastically great…[I]t was bookworthy. Which was very convenient, since I just happened to be a writer and recipe developer.”

Similarities between writing fiction and cookbooks: “I suppose the main similarity is that they’re both ridiculously hard,” Jackson said. “And they’re both creative endeavors, essentially. You never know what you’re going to discover. And both kinds of books are created incrementally, day by day, sentence by sentence, recipe by recipe. Writing fiction, however, is an artistic, contemplative, and internal process. Writing cookbooks is primarily an in-the-kitchen, mucking-around-with-food, making-so-many-dirty-dishes-you-can’t-believe-it process. In other words, they’re worlds apart.”

Favorite Recipes: “Oh, I’m not going to tell you which of my children are my favorites,” Jackson teased before revealing a few top choices:

Buttermilk Cornbread--the best basic cornbread in the land.

Popcorn Foccacia--made in part with popped popcorn that is ground into a fine flour, making a tender, flavorful, and unbeatable flatbread or pizza crust.

Peach Pie with Almond Crumb Topping--Danglicious to the max.

Maple Custard Tart--isn’t the title enough reason to like it?

The Ex-Boyfriend Cookbook, by Thisbe Nissen and Erin Ergenbright

Thisbe Nissen is the author Out of the Girls’ Room and Into the Night, which won the 1999 John Simmons Short Fiction Award, and the novels The Good People of New York and Osprey Island. Erin Ergenbright’s work has appeared in The May Queen: Women on Life, Love, Work, and Pulling it all Together in Your 30s and Alone in the Kitchen with an Eggplant: Confession of Cooking for One and Dining Alone. The two Workshop grads collaborated on The Ex-Boyfriend Cookbook: They Came, They Cooked, They Left (But We Ended Up with Some Great Recipes). The book features vibrant collages as well as recipes and the sometimes spurious stories of their origins.

Origins of the cookbook: Ergenbright recalls the moment the idea came to them: “Right after I graduated from Iowa, Thisbe and I moved into a sprawling old farmhouse ten miles outside Iowa City. Thisbe had been out of the workshop a year, and we both had just received Michener fellowships…Thisbe and I spent a couple months deep cleaning, spackling, and painting the farmhouse (while drinking bottles of Leinenkugel and listening to lesbian folk rock, and taking a break in the afternoons to get burritos in nearby West Branch). When the house was finally presentable, right around the Fourth of July, we planned a barbeque/potluck, and I told Thisbe, ‘I’m going to make Dave Haugaard’s Spicy Barbeque Rub.’

“We looked at each other, and said, ‘We should write The Ex-Boyfriend Cookbook!’ And that was that. And Dave Haugaard was a long-ago ex-boyfriend, and this was a recipe that asked you to pour spices into a Ziplock, put chicken in the bag, and shake it. I was not (and am not) much of a cook.”

Similarities between writing fiction and cookbooks: Nissen: “I’ve come to think that nearly everything I do proceeds via similar processes: I collect, I snip, I arrange, I rearrange, I clip, discard, re-re-rearrange, stitch, glue, paste. Collaging, writing, and quality—three things I do—are incredibly similar arts in my world. Each has its own rules, strictures, confines, freedoms, materials, but really, it’s all the same thing: patching together collected pieces and cohering them into whole entities unto themselves.”

Ergenbright: “I suppose the process of writing the cookbook was similar to writing fiction in that each story had a tiny kernel of truth (and a few were the whole truth, because they were stories that had to be told) that we fleshed out and brought to life. And one of the largest fictions of the book was that all these men had cooked for us—in reality, the recipes were mostly our mothers’.

“Since my time at Iowa, I’ve actually moved away from fiction, and become much more interested in nonfiction, but I think this process had what my favorite fiction writing experiences had—a sense of levity and possibility, and the pure pleasure of visualizing and creating a world and its inhabitants. But then again, looking at many of the stories I wrote, there’s a definite blurring of fiction and nonfiction, and I’m seeing those pieces as the precursors of my current work (though the focus is, thankfully, different).”

Favorite Recipes: Nissen: “We didn’t really test the recipes very well (read: at all). We weren’t in it as cookbook authors, per se. If we had it to do over, we ‘d definitely test the recipes and organize them in some reasonable fashion, with a damn index so a person I always hope someday one of us will get famous and someone’ll want to reissue the book and we can make it better.”

Lucas Ammarati’s Gazpacho: The one I use the most, since it’s my mother’s recipe, and I love it. Though the one in the cook book is too vinegary. I use less. It’s a good gazpacho recipe, if you can find it in there.”

Ergenbright: “Some of them I love for their collages, and some for their stories, but I think the sad ones still resonate most with me—the ones that seem a little like time capsules.”

Trenton Haverford’s Lasagna: “No one else has ever made me act like a blindfolded stalker, certain I’d eventually see the things I was looking for in him. He was the kind of guy that makes you smack your forehead, hard, hissing at yourself, ‘Stupid, stupid, stupid!’”

Sam’s Apple Crisp: It’s a beloved recipe from childhood, the collage features my beloved and now deceased black cat, Sinclair (whose image appears repeatedly in the cookbook), and the images bring me right back to living in Iowa.

Further reading:

Domesticity, by Bob Shacochis

Award-winning author and Writers’ Workshop alum Bob Shacochis wrote the “Dining In” column for GQ. The columns were collected in Domesticity: A Gastronomic Interpretation of Love. The book includes 200 recipes.

The Lee Bros. cookbooks

Ted Lee, one half of the famed Lee Bros., is a graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop.