Marathon to France

“In 1961, in love with the light, the landscape, and the odor of Provence, I bought an abandoned property near Sollies-Toucas….”

– Richard Olney, The French Menu Cookbook

Today, the words are printed everywhere; they’re ubiquitous, their meanings diluted and thinned to the consistency of a watery potage: Local. Artisanal. Authentic. Seasonal. Fresh. Simple. Long before American marketing geniuses and international mega-corporations green-washed and pre-packaged the very descriptors that defined the way the French have eaten and lived for a thousand years, one small-town Iowa man --- radically and even rigidly devoted to gastronomic perfection and Gallic tradition, and cloistered in the herbaceous hills not far from the Provençal city of Toulon --- was at the root of a movement that has forever changed the American culinary vernacular. Opinionated, often curmudgeonly, and unwavering (as curmudgeons often are) in his profound commitment to the tactile, sensory act of cooking, Richard Olney was emblematic of the best of Iowa married to the best of France: connected to the land, the earth, and what springs from it, and devoted to the practice of the table in the most intellectual, cerebral, and poetic of ways.

Born and raised in the tiny northwestern Iowa community briefly studied at the University of Iowa before leaving for New York, where he trained to be a painter at the Brooklyn Museum School. In 1951 – a time when gay New York intelligentsia was flocking to Paris; he called the writer James Baldwin his petit-ami and hobnobbed with W.H. Auden, James Jones, John Ashberry, Ned Rorem, Kenneth Anger, and others – Olney left the States forever and, after a decade in the City of Lights, moved permanently to his beloved, crumbling stone farmhouse in Soullie-Toucas. It was here that Olney remained, living a contradictory existence that was one part monastic, one part hedonistic: he foraged for fresh herbs in the hills around his home, cooked seductively (and often scantily clad in a hankie-sized bathing suit, denim shirt, and mangled espadrilles) with the seasons out of a massive stone fireplace, paired an extraordinary cellar packed with the greatest French wines ever produced with multi-course menus that ran the gamut from simple to rustically, deceptively complex; he worked, dined, and gossiped (bitched, to be clear) endlessly with and about the world’s culinary elite --- M.F.K. Fisher; Julia and Paul Child; Simca Beck; James Beard; Craig Claiborne; Elizabeth David.

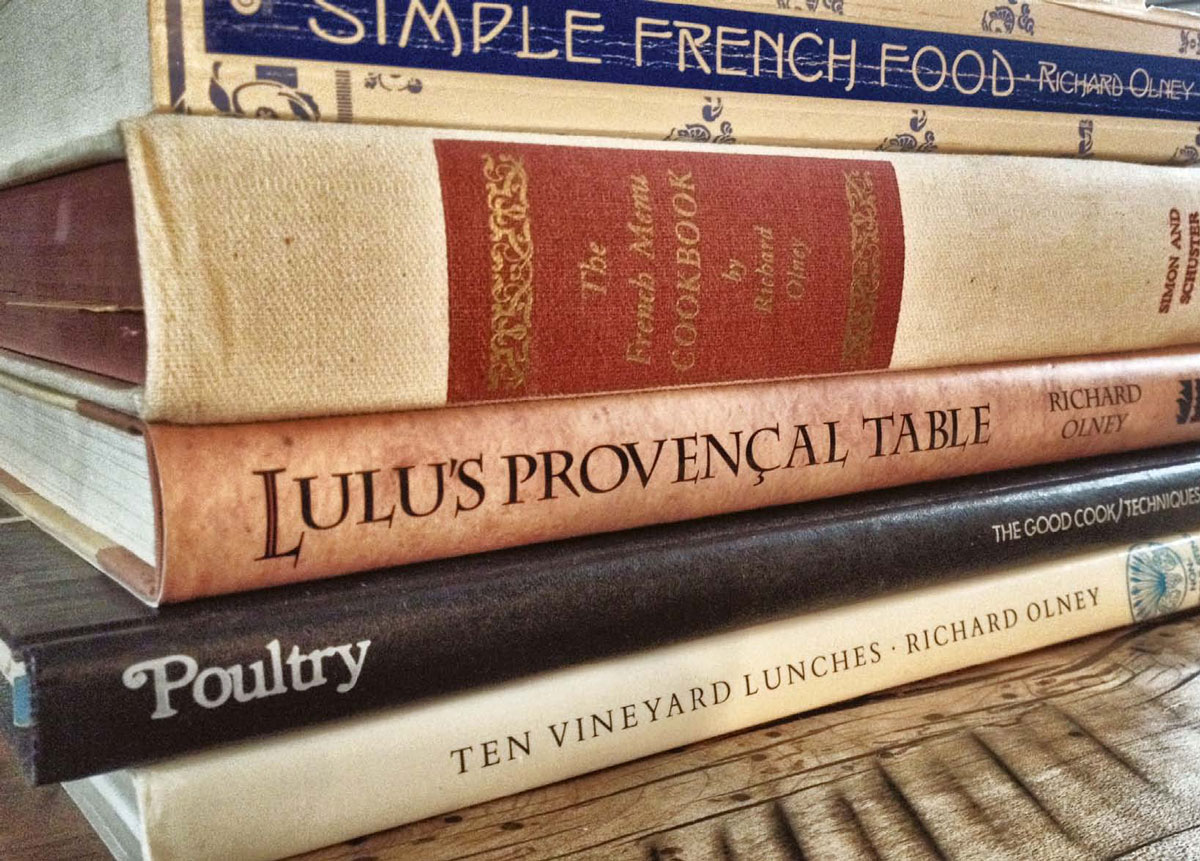

Here, on a manual typewriter, Olney wrote the many books that would change the lives of countless American chefs and restaurateurs who became devotees of authentic food, wine, process, and seasonality: he edited the landmark, 28-volume Time-Life series The Good Cook (1977-1982), wrote Lulu’s Provencal Table (1994), in which he not only introduced the earth-bound life, food, and wine of Lulu Peyraud, kitchen doyenne of Domaine Tempier, but brought her family’s world-class Bandol to a new generation of readers and oenophiles; Yquem (1986), an oversize paean to the miraculous gold Sauterne that dates back to the 1700s; Romanee-Conti (1995), a history of the mythic Burgundy so rare that a precious few have ever had the chance to drink it; and, among many others, this writer’s favorites, Simple French Food (1974), and the Talmudic The French Menu Cookbook (1970), a stained copy of which has stood in the kitchen at Chez Panisse for more than forty years, as well as my own since I acquired my first copy, two decades ago.

It is in the latter that Olney --- the original locavore before there was a word for it --- declares his unwavering devotion to seasonality:

The pages of this book are a loyal reflection of my life in the kitchen and at the table over the last twenty years. The seasonal form into which it has been cast emphasizes my intense conviction that, despite midwinter tomatoes, strawberries, asparagus and green beans, and the plethora of “fresh” frozen products on the market, one can only eat marvelously by respecting the seasons; each is sufficiently rich to afford a perfect table the year round, and the excitement of eating a freshly picked fruit or vegetable at the peak of its seasonal richness is forever deadened by the dull and listless year-round absorption of its shadow. (pg 15)

More than two-hundred pages later, Olney, in a recipe for poached chicken mousseline, utters one of the singularly most memorable lines ever published in any cookbook written by an American author and meant for an American audience:

“The chicken, at this point, is turned completely inside out.”

Since his death in 1999 from heart failure, Richard Olney has been culinarily canonized, demonized for his often prickly and polarizing opinions about his colleagues, and ultimately lionized in a manner that he – ever the private, intellectual Iowan possessed of a poetic hand with forcemeat and pot-au-feu – would arguably have found flattering, if not a tad intrusive. For us, his legions of readers and cooks, we are left with his gifts, and with them, the knowledge that the local, authentic food movement as most Americans know it today began not in our beloved, Mecca-like Berkeley, but in a small town of 600, in a quiet corner of Iowa, called Marathon.

Richard Olney Bibliography

The French Menu Cookbook: The Food and Wine of France—Season by Delicious Season—in Beautifully Composed Menus for American Dining and Entertaining by an American Living in Paris and Provence (1970)

Simple French Food (1974)

The Good Cook’s Encyclopedia (1977-1982)

Yquem (1986)

Ten Vineyard Lunches (1988)

Provence, the Beautiful Cookbook: Authentic Recipes from the Regions of Provence (1993)

Lulu’s Provençal Table: The Exuberant Food and Wine from Domaine Tempier Vineyard (1994)

Romanée Conti: The World’s Most Fabled Wine (1995)

Cooking for Two (1996)

Richard Olney’s French Wine and Food: A Wine Lover’s Cookbook (1997),

Reflexions (1999, posthumous)

Elissa Altman is the author of the critically-acclaimed food memoir, Poor Man’s Feast: A Love Story of Comfort, Desire, and the Art of Simple Cooking, and the James Beard Award-winning blog of the same name. Her upcoming Treyf: A Story of Hunger and Transgression will be published in 2015 (Berkley Books).