The 1908 Knoxville Ladies P.E.O. Cookbook, Revisited

No one who cooks, cooks alone. Even at her most solitary, a cook in the kitchen is surrounded by generations of cooks past, the advice and menus of cooks present, and the wisdom of cookbook writers. Laurie Colwin (1944-1992), American writer and cook; author of Home Cooking and More Home Cooking.

In the opening pages of her remarkable 2003 book, “Eat My Words: Reading Women’s Lives Through the Cookbooks They Wrote,” Janet Theophano presents a story of the discovery of an early nineteenth century manuscript of recipes apparently authored by one Jan Janviers, only to find the recipes inside revealed the handwriting of many different women, a truly communal effort. Theophano concludes that while many historical cookbooks claim a single author, they are truly collective works by a community made mostly of women. While cookbooks present foods certainly, they also are reflections of women’s social interactions. Scrutinized even more closely, cookbooks also present a wealth of information about history, culture, faith, the state of the economy and the structure of society. They can also be memoirs and travelogues.

Cookbooks are also just fun to look at and read--especially old ones. They’re like traveling through time. A couple of years ago, two friends from Knoxville, Iowa--Christa Belknap and Kay Jensen, introduced me to a cookbook published by Knoxville PEO ladies in 1908. The PEO (Philanthropic Educational Organization) is a women’s group that helps women in a variety of ways, including through scholarships. Christa and Kay are current members of the PEO in Knoxville, and took great pride in sharing not only the original cookbook, but also the version that was reprinted as a “Souvenir Edition” in 1992, as part of the Iowa Szathmáry Culinary Arts Series by the University of Iowa Press. According to series editor David E. Schoonover, the Knoxville PEO cookbook was selected for publication from a group of several hundred cookbooks in the University of Iowa Szathmáry Collection of the Culinary Arts, representing each of the United States.

To put the PEO Cookbook in historical context, in 1908 Theodore Roosevelt was president, a 46th star was added to the American Flag to represent the state of Oklahoma, Mother’s Day was first celebrated, Henry Ford produced the first Model T, the Chicago Cubs last won the World Series, and women all over the world were cooking and sharing recipes.

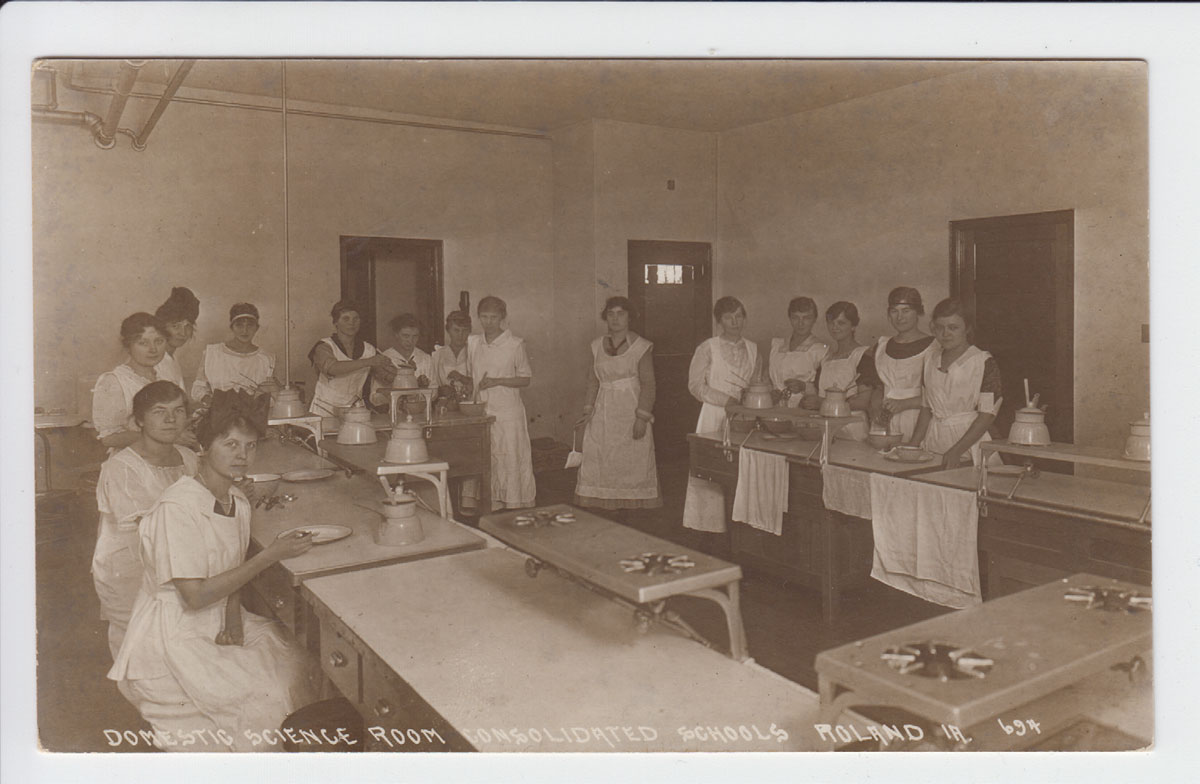

The period from 1890 to 1920 is well known as the “Progressive Era,” a period of social and political reform. More women were going to school, as in 1902 Iowa required compulsory attendance in school for all children from age 6-16. Furthermore, offset printing began in 1903- 4, making the distribution of printed material cheaper and therefore more widely available.

All of these convergent historical events may well have made the Knoxville PEO cookbook possible--with the included photographs of local landmarks. Kay and Christa hypothesize that the cookbook was written for fun, but that it was also useful as a handy guide for new brides. Further, the intellectual pleasure of experimenting with new recipes was very likely even more important than we can imagine, given that most if not all of the women contributing to the cookbook did not work outside of their homes. And of course, we have to consider how women achieved status in the community at the time. Prowess at cooking was certainly valued and it’s certain that the women competed with each other at the art and science, even if subconsciously. And while it seems sexist today, cooking ability at the time likely impacted a young woman’s chances of finding a “good” husband.

Sharing recipes has been a fact of life for millennia, as it is today. Only in 1908 there wasn’t a smartphone app for it. Sharing recipes among friends and neighbors and across generations was likely the most common way of learning something new, but not the only way.

It is unclear whether or not home economics or something like it was taught in the Knoxville area prior to 1908. Iowa State University was the first land grant university in the nation to offer coursework for credit in domestic economy in 1872. Yet, the American Home Economics Association (now called the American Association of Family and Consumer Sciences) wasn’t founded until 1909. The State of Iowa passed the Agricultural Extension Act in 1906, but a Home Economics Division wasn’t established until 1913, and departments were established at both the University of Iowa and Iowa State University that same year. The University of Northern Iowa established its Domestic Science Program in 1904. Iowa’s numerous private colleges may also have established programs at this time, and it is quite possible that the Knoxville PEO ladies may have been part of a historical wave that valued education about home life, including cooking.

Magazines may have also been a source for recipes for Knoxville women at this time. While the Knoxville Public Library wasn’t established until 1909, a variety of magazines may have been available for local women by subscription prior to the PEO cookbook publication. Good Housekeeping (established 1885), Redbook (1903), Ladies Home Journal (1883), and McCalls (1897) were likely found in ladies homes and recipes shared. Significantly, while not all of these magazines began with Meredith publishing in nearby Des Moines, they were eventually acquired by the company, a matter of pride to many Iowans.

There’s a comforting inexactitude to the recipes in the PEO book that at times seems to defy chemistry and physics. A “quick” oven might reflect the less accurate technology of the time, but also the fact that some women may have been cooking with wood. The instructions in the following recipes are all casual, implying a shared common knowledge that transcends the specifics of instruction standardized in recipes today. Notice that they are narratives, without the isolated list of ingredients we are familiar with today. All recipes presented are in their original wording and format.

Some of the recipes convey lost knowledge as well -- for example, the following recipe by Nora Neal.

Nagasaki Biscuit

One pint of bread sponge, one-half cup (small) sugar, butter size of walnut; mix these thoroughly, then add flour until almost as stiff as bread dough; let rise, then handle as little as possible, rolling it about one inch thick; spread with butter, sprinkle with sugar, commence at side and roll light and cut in rounds about one inch thick; place in a pan as biscuit, close together, let rise quite light, then bake.

Why Nagasaki? Did Mrs. Neal travel to Nagasaki and learn about these biscuits there? Did she make these biscuits in Nagasaki? Do other recipes for Nagasaki Biscuits offer clues? I Googled “Nagasaki Biscuit” to see if there were other recipes, but the only reference was to this very recipe in the on-line version of the book. Of course, 1908 is well before the 1945 atomic bombing of Nagasaki that made the city a household name, so that certainly didn’t play a role. So we’ll probably never know the origin of the name. And why “Biscuit” singular? A language convention? A typo?

I do love “butter size of walnut.” It’s evocative, almost poetic, and implies a closeness to the natural that is lacking today, not only in recipes but in life in general. I also love how inexact the measurement is when certainly more exact measures existed. Googling “butter size of walnut” I find the term common in cookbooks of the time, which makes me wonder about its origin, that too likely lost to the mists of time.

And then, of course, the instruction to “bake.” I must ask, how hot the oven? How long? I can imagine Mrs. Neal chuckling at me as she is sliding the pan of biscuits into her oven as I stand by her side posing these questions. “Well, hot enough, silly,” she says to me. “And until they’re done!”

Some of the recipes are remarkably simple. Mrs. C. Mulky offers:

Sweet Potatoes with Dressing

Pare sweet potatoes and put in one-fourth cup of sugar, one pint of milk and water together, one heaping tablespoon of lard. Put in all together and boil until done.

A mere two sentences. Of course, I have to ask how many sweet potatoes, and is it one pint of milk AND one pint of water, or half a pint of each? And it is quite likely that only a brave and confident cook today would admit to using LARD in our “heart healthy” environment, despite the fact that Mrs. Mulky and her family were likely healthier than most Americans today. Of course, we won’t ask how long to boil the mixture--”until it’s done, silly!”

Mrs. Mulky also presents:

Cold Slaw

Soak small head of cabbage in cold water one hour. Shave very fine, salt pepper and sugar to taste; stir with a fork, pour over this a small cupfull of thick sour cream and enough vinegar to suit the taste.

I heard both of the terms coleslaw and coldslaw or cold slaw growing up, and figured that one was probably correct, and the other a linguistic aberration, or regional variant. Culinarylore.com tells us that the term coleslaw comes from the Dutch koolsla, meaning cabbage salad. The kool was anglicized into cole, and since the dish is served cold, confusion ensued and both coleslaw and cold slaw are used. Most recipes today simply call for mayonnaise, and while this makes it easy to make, many cooks dip it from the purchased jar or even worse, squeeze it from a bottle. Not to put too fine a point on it, but yuck. Note there is no egg in this recipe, or lemon juice, or mustard, as is common in coleslaw recipes today.

Note that we are to add ingredients to “suit the taste.” This is common in the book, salt, sugar, pepper, and herbs to “suit” the cook’s taste.

I include the following recipe by Mrs. P.M. Stentz for a couple of reasons. First, while one can find contemporary pressed chicken recipes, I’d never heard of it. The improbability of serving so many people with three chickens was intriguing as well, and the recipe is just darn interesting.

Pressed Chicken for Fifty

Three large, fat hens, thoroughly cleaned and cooled, salt and cook until very tender. Cook down well in broth. Separate the light and dark meat, and grind through meat grinder. If broth is rich skim off a part of the fat, and add a lump of butter to flavor, then add one quart of cold water, let heat and use to mix meat. Take white meat, season well, add liquor, let it take up all it will. Take dark meat season with salt, pepper and celery salt, then add liquor, mix very soft, measure your meat, put one bowl of white meat in pan and press, then one bowl of dark, and so on until all is used. Press gently with the hand and let it cool. Do nor (sic) put on a weight.

Alternating ground dark and light meat and pressing is fascinating. I guess adding a weight would just be too much pressing. Nevertheless, other references suggest that Pressed Chicken loaf was evidently a southern summer classic with German roots, a make-ahead dish served cold with bread and a relish tray, perhaps.

Finally, many of the recipes include combinations of food that are uncommon today. Mrs. Burnie Woodruff offers an example.

Chicken and Green Corn Pie

Slice the corn from twelve tender but well filled ears and scrape the cobs well. Have ready one chicken nicely fried, one pint of fresh milk, one gill of sweet cream, two ounces of butter, three fresh eggs. Put one-third of the corn in the bottom of a baking dish, sprinkle with salt and pepper, using one third of the butter cut into bits. Lay over this one-half of the chicken. Add another layer of corn, salt, pepper, butter, and chicken. On this put the rest of the corn, seasoning and butter. Beat the milk, eggs and cream together and pour over the pie just as you are ready to put it into the oven. Bake thirty minutes and serve at once.

“Well filled” ears of corn is a term out of use, I suspect, but suggests the length that the cook would go to select quality ingredients. The direction to scrape the cobs well implies either not to be wasteful or that the part of the kernels close to the cob adds something to the taste of the dish. I hadn’t heard the term “gill” before, but apparently it is still used in measuring alcoholic spirits. A gill is a quarter of a pint. And of course, this dish is essentially a savory custard base with a few extras added.

Intellectualizing cookbooks is fun; they are full of thick meaning that can be teased out, that gives us clues as to where people have been and the lives they led. And if we put their recipes to work in our own kitchens it’s almost as if we’re cooking side by side with them. And be sure to use only well filled ears, and scrape the cob well. Season to taste.

Remember, no one cooks alone.